Publishing note: This article was supported by funding from the Pittsburgh Media Partnership. It is the second in a series on pollution and misinformation in Greater Pittsburgh from a consortium of outlets including Allegheny Front, Ambridge Connection, The Incline, Mon Valley Independent, Pittsburgh City Paper, Pittsburgh Independent and Pittsburgh Union Progress. Read the first in the series in the Pittsburgh Independent and stay tuned for more.

As Greater Pittsburgh residents fume over ongoing poor air quality, locals documenting their lived experiences with pollution have propelled demands for answers. These grassroots scientists are filling in gaps in the media landscape and compiling a growing body of evidence for the benefit of regulators who keep tabs on high-emissions facilities, among them Shell’s Potter Township chemical plant.

Pollution events such as the Norfolk Southern derailment in East Palestine, OH have newly alerted some Beaver County residents to the inherent dangers of local industries, but residents including South Heights local Bob Schmetzer were already wary. Recent flaring events at Shell added to his fear of catastrophic health impacts. Schmetzer, a volunteer with the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community, says the combination of combustible rail shipments and vulnerable petrochemical infrastructure could prove deadly, as it nearly did in 2018.

“People need to get a grip on this,” he says. “We’re living in a dangerous area.”

Grassroots science can take many forms. When it comes to air quality, sometimes it’s as simple as watching (and smelling) what polluters are doing.

Melanie Meade, a Clairton resident, says volunteering with the Group Against Smog and Pollution (GASP) has empowered her to speak up about air pollution’s impact on public health. “There are other people who could possibly be having the same experience and never attribute it to pollution,” she says. She hopes her experience in the Mon Valley can empower residents in Beaver County to better understand the potential health impacts of living near a major source of harmful emissions.

Lessons from the Mon Valley

Over the past decade, GASP has regularly trained small cohorts of smoke readers who use their eyes and a chart to keep tabs on what comes out of chimneys in Southwestern PA. There are two advantages to this system: it doesn’t require much equipment, and it uses the same legal threshold the Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD) uses to determine if a polluter has broken the law.

Smoke reading has allowed Mon Valley residents like Meade to update neighbors and get a better handle on the air pollution in their backyard. Her son plays basketball in full view of Clairton Coke Works, the region’s largest polluter.

“I have to tell him all the time, ‘oh yeah, it’s a yellow air quality day, an orange air quality day, a red air quality day.’ Most of our children and coaches don’t know that means something,” Meade says. “When we’re out here, his nose is constantly running.” She suspects air pollution has been a factor in health difficulties she and many of her family members have experienced.

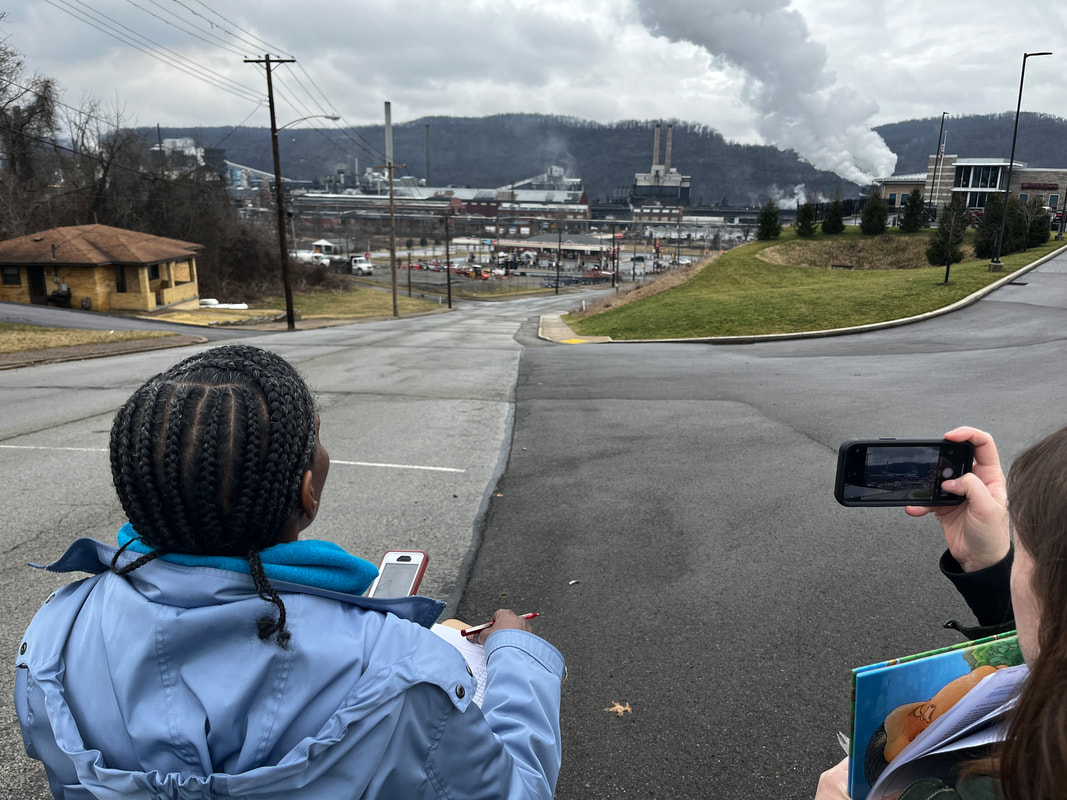

Beaver County resident Clifford Lau, an industrial scientist, joined GASP volunteers including Meade in February to learn more about smoke reading. Lau fears the Shell chemical plant could bring similar health and environmental impacts to the Ohio Valley as it continues to pollute beyond legal limits.

“If you have a bad inversion day, [Shell’s emissions] are just going to stay right down in our valley,” he says. Lau has been in contact with the Southwest Regional Office of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to share his concerns.

The process Meade, Lau and other volunteers use to watch Clairton Works is relatively straightforward. At regular intervals, standing so the sun hits the factory’s columns of steam and wisps of thick yellow smoke, they mark the opacity of smoke on a printed table while noting other environmental factors.

Suzanne Seppi, who has worked with GASP in various capacities for over 20 years and organizes smoke readings, says “the naked eye can do a pretty good job of saying what the opacity of a plume is.” If a plume equala or exceeds an opacity of 20% for a period or periods aggregating more than three minutes in an hour--or equals or exceeds 60% opacity at all-- it's in violation of the rules. Smoke readers can then submit reports to the Allegheny County Health Department.

Erin Mallea, another GASP volunteer, graduated from Smoke School and has used smoke reading and sample collection in an ongoing art project. “Our readings today couldn’t be used to submit a violation. It has to be [ACHD],” she says. “It’s hard to use to hold the company accountable, but it is a way to have ongoing documentation you can send to the health department.”

| Smoke reading has other limitations. While a smoke plume’s opacity is a potential indicator of Particulate Matter, or PM2.5, density, it doesn’t speak to the Volatile Organic Compounds, or VOCs, it might contain. However, volunteers can make educated guesses based on a plume’s color. Certain smells can also be red flags for toxic emissions—indeed, it was a “maple-syrup-like odor” that initially alerted some residents to the Shell plant’s disruptive potential. Lau has since received EPA funding to monitor air and water quality in the Ohio Valley. “The Shell plant’s not like this,” he says. “One would not expect any smoke at all from the Shell plant. However, in the last couple of months, we’ve had some flaring events that have produced quite a bit of smoke.” As those flaring events continue, smoke reading has become one in an arsenal of tools locals are using to hold polluters accountable. A multi-pronged approach Downriver on Neville Island, smoke reading helped focus attention on the Shenango Coke Works’ pollution levels in the mid-2010s. Though the company denies grassroots science was a factor, the plant closed in early 2016 after considerable public pressure. Afterward, area residents’ health measurably improved. Much of that pressure came from Allegheny County Clean Air Now, or ACCAN. Angelo Taranto joined ACCAN in 2014 and says the process of smoke reading and regular correspondence with environmental groups, county officials and eventually the EPA, combined with a live camera feed, eventually led to a critical mass of evidence that tarnished Shenango’s brand. Neville Island remains a site of pollution—and Taranto remains vigilant. Ohio Valley residents’ attention turned from Shenango to area recycler Metalico, a Chinese-held firm that shreds automobiles for scrap. “When they shred cars, they’re not real careful to remove antifreeze, fuel, oil, things like that,” he says. “Neighbors across the river were getting hit with horrific odors, explosions that shook their houses and clouds of dust.” |

Taranto stresses a multi-pronged approach. Standing near a battery of equipment in Emsworth, he has a clear view of Metalico, where the car shredder emits columns of steam that separates from wisps of thick blue smoke. Nearby, a PurpleAir monitor for PM2.5, a larger device that measures VOCs and a camera from the CMU CREATE Lab record a 24-hour feed of Metalico’s emissions. These devices can supplement and corroborate an in-person smoke reading. GASP and other groups say the more data locals can collect, the better.

“There are a lot of things that can be done. Smoke reading is an important part of the citizen science toolkit,” GASP’s Seppi says.

Taranto says the problem isn’t getting good data, but getting government officials to act. Following a fire at Metalico, Taranto says ACHD has been slow to return calls, and ACCAN instead turned to the EPA, which took action against the company late last month.

In the meantime, Taranto and other volunteers have continued their work. They’ve begun using summa canister sampling to measure VOCs and responding to smell complaints in nearby McKees Rocks. However, all this data is only useful if it is acted upon at the county level. Taranto feels ACHD has been overly optimistic when it comes to regional air quality.

“Our impression is they haven’t really wanted to come down hard on industry,” Taranto says.

“Penalize this behavior”

Matt Mehalik of the Breathe Project says grassroots science has been critical to local efforts to rein in air pollution, especially as climate change exacerbates the temperature inversions that trap the pollution close to residents. However, Mehalik says the county has raised barriers to community input.

“[ACCAN], when they were documenting pollution from Shenango, were able to have regular meetings with ACHD experts and provide info in dialogue with them,” Mehalik says. “All of that dialogue has been completely shut down.”

ACHD said they’ve moved to an online platform in part to streamline the reporting process for concerned residents. The county has added air quality reporting to its support center and recently published a monitoring site for hydrogen sulfide concentration.

ACHD’s deputy director for environmental health, Geoff Rabinowitz, says delays in responding can reflect the multistep nature of the department’s permitting responsibilities.

“As a regulatory authority, that’s a lot of what we do: writing permits, working on facility compliance, using enforcement to compel that compliance,” Rabinowitz says. “When we do those permitting activities, we have to follow the process to ensure we’re doing so in a legal manner.” He says delays in communication often mean the agency is trying not to jeopardize ongoing enforcement actions.

Some area residents are opting to take their experiences straight to the public. CREATE Lab’s SmellPGH app has become a popular way for residents to report smells. SmellPGH often reflects high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide in the air, which can be an indicator of other pollutants. Each day’s data is sent to the ACHD in a daily rundown. Though the county doesn’t use SmellPGH data “quantitatively” because of its subjectivity and the complexities of how pollution is regulated, Rabinowitz says it can corroborate GovQA reports or other issues with the “qualitative” data from SmellPGH.

Meanwhile, artists and documentarians are finding other ways to address air quality. Mallea’s artwork in her new exhibition “Permissible Dose” gathers video footage of smoke reading, recreated odors, synthetic bricks of coal and other objects that paint a holistic picture of regional pollution and the barriers to documenting it. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh filmmaker Mark Dixon, in addition to helping install PurpleAir monitors near the Shell plant, is working on a documentary of the region’s ongoing issues with temperature inversions.

“Plastic is not a handled situation—it’s causing problems in the placenta and crossing the blood-brain barrier,” Dixon says. “We have to become tolerant of all those negative outcomes if we think it’s not important to fight against Shell.”

The infrastructure in Beaver County presents barriers to residents seeking changes from heavy polluters. Anaïs Peterson of BCMAC’s Eyes on Shell group group says beyond flaring events and smoke, the massive ethylene plant is extremely bright at night and can be very loud: “That’s something that’s come up with watchdogs—folks outside Potter Township have noise and light concerns, but only the Township can regulate that.” Peterson says Shell has begun providing some air quality data in response to resident concerns.

But the most obvious barrier to further regulation in Beaver County is the lack of any health department. Andie Grey of Eyes on Shell says Beaver County officials have adopted a mostly “hands-off” approach. Without more action, she says area residents face both direct health effects and ongoing uncertainty about their new “unruly neighbor.”

Grey hopes state officials will step in, but worries Shell will fall into a “pay-to-pollute” cycle. “It’s important that the DEP exercises their full regulatory power and does everything within their power to penalize this behavior,” she says.

Taking action

Shell is under growing scrutiny both in Beaver County and internationally. ClimateEarth, a London-based climate law firm, filed a lawsuit against Shell’s board of directors last month alleging inaction in the face of climate change. In Potter Township, meanwhile, lawsuits are underway, and environmental groups are encouraging residents to pay close attention. Volunteers say a steady drumbeat of citizen feedback will push officials to act.

“That’s what keeps me motivated to keep working at this problem,” Dixon says. “We have to keep working at our collective tolerance of being polluted.”

“Really what's important is affirming people’s experiences with the [Shell] plant,” says Peterson. “You don’t need to be chemist to look at the February 13 flare and say, ‘something’s wrong.’” Peterson likewise encourages residents to call their hotline, email the group, or message Eyes on Shell on social media. There’s now a 24-hour Eyes on Shell hotline where residents can report their concerns.

Advocates say the data speaks to rising concern among area residents. They urge regulators to listen to what the data and local watchdogs are saying. “Above and beyond all else, listen to people and what they're dealing with on a daily basis,” Mehalik says. “Smells that wake people up in the middle of the night, affect people’s health, disrupt the community regularly—that’s unacceptable.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the opacity values used by smoke readers to determine violations. The error has been corrected.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed